There’s a healthy market for open data repository software. There’s ArcGIS Open Data, CKAN, DKAN, Junar, OpenDataSoft, and Socrata. It might not seem like there’s space in the market for a new contender, and yet a new entrant makes a good argument for its own necessity.

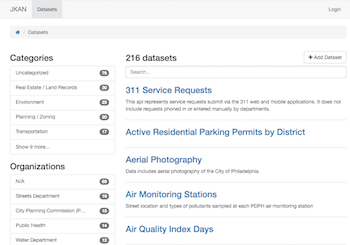

Philadelphia CDO Tim Wisniewski has created JKAN, a data catalog modeled on CKAN, but built in Jekyll. The GitHub-friendly, Markdown-based website generation system has made static sites popular again, especially when coupled with the power of JavaScript, and Wisniewski has used it to make a simple, lightweight data catalog.

Via email, I asked Wisniewski a few questions about JKAN.

There are a bunch of data repository options out there. Why create something new?

Just about every government website has data on it already. The first version of OpenDataPhilly was basically a card catalog of links to data that the city government published. What that did was connect the dots between disparate datasets, so people could see the picture that it formed, and what the benefit was, resulting in enough momentum for an open data program to form inside the government, with resources behind it.

That step is really important for getting open data off the ground in cities. Robust APIs, data standards, and in-depth analysis tools come later.

The idea behind JKAN is to make this step really easy, and enable a champion for open data in a government agency to do this themselves, without needing tens-to-hundreds of thousands of dollars allocated first, or having to set up servers at the command line.

Architecturally, JKAN is quite different from other repository software. But its modularity, simplicity, and static nature fit into a larger trend in software. Could you tell me about the decisions that went into designing and creating it?

The core functionality of a data catalog is making it easy to find datasets and the links to download them. JKAN accomplishes this without needing a database. Under the hood, there are a bunch of text files that represent each dataset, and contain its title, description, download links, etc. When you modify one of those files, JKAN regenerates the website using the text files. The website can then be served over a simple web server, because they’re just HTML files. JKAN goes a step further and provides a user-friendly interface for modifying the text files. Because of this simple architecture, you can run a JKAN site for free on GitHub.

What’s missing is a “data store.” Data stores allow users to actually upload the data rather than just link to it. These are helpful, but account for the majority of the cost and headache. For now, why not just put your data on Dropbox, Google Drive, an FTP site, the city’s website, or even a GitHub repo? Sure, those options won’t give you robust APIs, but that probably shouldn’t be your top priority if you’re trying to get an open data program off the ground anyway. Philly hosted most of its data on GitHub for the first year of its open data program, before purchasing a data store, and even today, the data store and data catalog are two distinct products.

Have folks from other governments expressed interest in JKAN yet?

Well, to be honest, I started it as a proof of concept. The recent addition of user-friendly interfaces for editing the datasets, though, has got me thinking that it could actually be a thing. I’ve been developing it in the open on GitHub, but there are still a few features I’m working on before it’s ready for production use. Now would be a great time for collaborators to jump in, though, if anyone’s interested.

What does success look like for JKAN?

- Standing up a simple data catalog is no longer a barrier for a government’s entry into open data, so they can focus on the hard parts like getting buy-in.

- A few more folks get behind it and help make improvements and bug fixes, so folks are comfortable enough to use it

Of the work remaining to be done, are there folks with any particular skill sets that you need help from, or individual issues that you’d like to see people tackle that are perhaps outside of your skills or time capacity?

I’d love for someone to think about the user experience from the ground up. The layout, terminology, and functionality is almost entirely based on (a slimmed-down version of) CKAN. And for folks familiar with CKAN, this is comfortable. But how would we design a data portal that also caters to people who are new to open data? If the purpose of the product is to demonstrate the value of open data, how can its design further that? JKAN is also sorely lacking in aesthetic and would greatly benefit from some web design.

For more information about JKAN, or to contribute to it, see the project’s GitHub repository, or follow the one-step guide to have your own repository running in literal seconds.