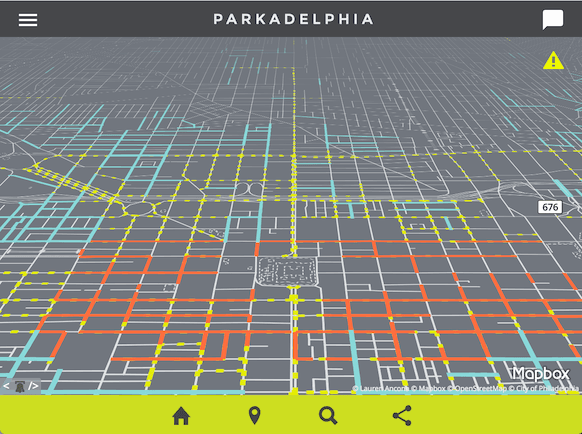

Last month, Lauren Ancona created an entirely new type of website: a mapped open-data powered parking website for Philadelphia, named “Parkadelphia.”

Ancona is the Senior Data Scientist for the City of Philadelphia, but she built this website on her own time, as a passion project. I asked her a few questions about this novel form of open data.

Where did you get the idea for Parkadelphia?

It wasn’t as much of an idea as it was just a hole that needed filling. I just couldn’t understand why, in an age where I can poke at my phone and a person in a car shows up to drive me wherever I want, I couldn’t also use it to figure out where it was legal to park, for how long, and how much it would cost me. It turned out to be an excellent vehicle for learning to code, as an autodidact. You have to find some way to limit yourself to a defined set of goals, otherwise you never end up producing something from start to finish.

What datasets are required for this?

In Philadelphia, we’re using:

- Streets Centerlines (maintained by Streets Department)

- Residential Permit Parking Blocks (joined from text-only file)

- Residential Permit Districts (created manually from text of the City code)

- Metered Blocks (joined from text-only file)

- Scooter/Motorcycle Corrals (created manually from list on Philadelphia Parking Authority website)

- Loading/Delivery Zones (created from text file)

- Snow Emergency Routes (maintained by Streets Department)

- Center City Parking Meter locations (created manually from Google Street View)

Some cities have still other sets available that may be useful, such as:

- Fire Hydrant locations

- Parking Meter locations

- Handicapped Parking Spot locations

- Car Share locations

Is it unusual that Philadelphia publishes the data necessary to support this?

Most of the data that has been released in Philadelphia isn’t actually geospatial…so, no? In fact, many other cities, including Washington, DC and San Francisco, already publish most of the data you’d need to build something similar via their open data portals. The trick was finding some way to tie the regulations together and refer to existing geometry. Most large cities keep their own canonical data set of streets and their exact geometry (relative to one another), called a centerlines file (sometimes “streets centerlines”). Because hundred blocks often intersect other, smaller segments, they become subdivided into smaller sections—called “street segments.”

I decided to try to use that resolution and join the regulation data I had to each street segment, which each have a unique ID. While it’s true that this model doesn’t take into account regulations like minimum legal distance you can park from an intersection, it was enough to get started. Philadelphia has over 40,000 street segments; if I needed more detailed information after that I figured it could always be tightened down later.

I’m looking at using something like Koop to take a shot at loosely coupling sets directly from data portals that have the minimum required sets, to see if I could handle any necessary joins on the fly, with something like Turf.js, cache the regulations for a period of time, serve via API to any apps that wanted to reference them. Then perhaps depending on how frequently they might change, just go back to the portal at a set interval to refresh the data automatically. But I need to finish a data model for that, first.

One exciting development since we launched is the beginning of a conversation between cities to establish a spec for open parking data. It’s my nerdiest dream yet, but what if we could build something like GTFS, but for parking data? If you can look up the subway schedule via a search engine, why can’t you look up public parking regulations?

What would it look like to deploy this in other cities?

If there’s a centerlines file available, I’d start there. Then find a way to start mapping regulation data to the smallest linear segment you have available—likely segment.

I’m working to document the data model—it was constantly changing right up until launch—in a way that is general enough that would be easy to reuse.

Maintainability is a huge concern—it’d be best to plan your model around the most convenient way to update some (but not all) of the data on a rolling basis, since that’s been the most likely scenario, in my experience.

To contribute to Parkadelphia, or to fork it to deploy in your own city, see the project’s GitHub repository.