An open data armageddon is upon us for state legal data, in the form of the Uniform Electronic Legal Materials Act (UELMA, pronounced “you-EL-mah”). The model legislation is being adopted by states throughout the nation, requiring them to make published legal data verifiable, so that people know that it is official, authoritative, and unchanged. On its current course, the law will effectively force states to publish legal data as PDFs, bringing to an end an era of expanding the availability of legal data.

So U.S. Open Data stepped in, creating a simple, free, open source software product that won’t just prevent this from happening, but will accelerate the trend towards open state legal data. This is the story of how that happened, and the lessons to be learned from it.

Early last year, Washington D.C. Council attorney David Zvenyach approached us with both a problem and a solution. A member of the Uniform Law Commission, Dave was familiar with UELMA, and worried that its implementation could set back open data.

UELMA requires that states publish legal data in a method that is verifiable, which is to say that a person with a copy of a regulation (for example) must have some method of knowing that it is an actual regulation and not a fabrication. It’s this bit that does that:

To comply, many states are simply looking at publishing all laws as PDFs, using Adobe Acrobat to digitally sign each PDF. That would be a cheap, easy way to comply with the law, with the downside that it could be the end of legal data within states. That’s because an authentication system based on Acrobat cannot be applied to anything other than a PDF, like JSON, XML, YAML, etc. That would be catastrophic for open data. As states adopt UELMA, they have a year or two to figure out how to implement it, providing a brief window in which this disaster can be headed off.

Dave’s idea was to create a simple, lightweight file authentication system. After all, this is a problem solved many times over in many other domains. Every software update downloaded by Windows, Mac OS, Android, etc. all uses a basic authentication process to ensure that the software update is official and unchanged. (For the technically inclined, imagine verifying an MD5 hash over an HTTPS connection.) We knew this was both plausible and palatable to states, because Minnesota’s Office of the Revisor of Statutes had built a similar system in-house, and published a crucial, detailed whitepaper about how they did so. (Minnesota initially bid out the project, and was so appalled by the quotes that they received that they decided to just build the system themselves. Brava to the Minnesota Revisor of Statutes for a bold decision.) Such a system would allow any file to be verifiable under UELMA—not just PDFs, but also JSON, XML, YAML, Word, etc. This would simultaneously solve the problem of government agencies that refuse to provide data because “somebody could change it,” by providing them with a verification mechanism. This would allow us to turn UELMA from an accidental cudgel against open data into a powerful tool in favor of it.

A real problem, a sensible solution. U.S. Open Data was on it.

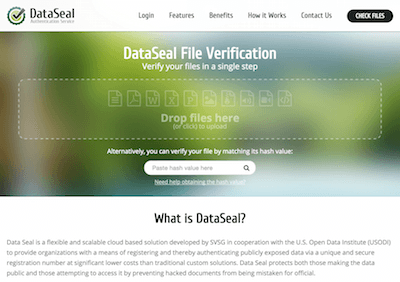

Silicon Valley Software Group won the contract. Mike Tigas and Dan Schultz started committing code at the end of April and they finished by June. The whole project cost just $7,500. Throughout the process, Washington D.C. served as the client stand-in, courtesy of Dave. All work was done on GitHub, and hosted on the collaboratively-maintained /unitedstates/ GitHub repository as a sign of our committment to a larger cooperative goal. We named the product “Data Seal.”

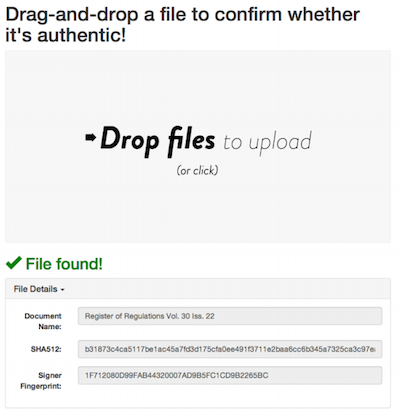

The way it works is easy. Data Seal is a self-hosted website that governments can add documents to. Data Seal generates a PGP signature for each file that’s added. Then, when a user wants to verify the validity of a legal material (e.g., a copy of a law), they can visit the agency’s Data Seal website, drag the file onto their browser, and find out whether the document is official or if it’s been altered. (The document-adding and document-verification processes can be performed via the browser or through an API.)

In July I presented the finished product to the Administrative Codes and Registers conference, exhorting members to use Data Seal as UELMA passed into law in their states, or to follow Minnesota’s example and write the code themselves. My message was simple: file verification is a trivially-solved technological problem.

But we knew there remained a major obstacle: that free software is basically worthless to government agencies.

Governments acquire technology by publishing RFPs and awarding contracts. Developers of open source software aren’t in the habit of responding to RFPs with bids of $0 that say “just go ahead and download my software and use it.” Many agencies lack the in-house knowledge about how to install software, or don’t have the ability to use the services required. So instructions like “throw this up on a Heroku instance, set up a Mailgun account and plug your API key into the config file, which should live on S3” are somewhere between baffling and logistically impossible.

Although Data Seal is simple to install by many developers’ standards—it’s a basic Django application that uses GnuPG and a Python GnuPG wrapper—it falls into the category of “Free As In Helicopter”—it costs nothing, but requires so much knowledge about how to set up and operate as to be implausible.

Solution: Make it possible for governments to pay for our free software.

So late last year we went back to Silicon Valley Software Group, the vendor that built Data Seal, and explained that—congratulations!—they were now the world’s leading experts in Data Seal, and consequently in a great position to sell hosting services. (Of course, anybody could sell Data Seal hosting services—it’s free software.) They thought that was a fine idea, so they went away for a while and worked on what to do about that.

As of today, Silicon Valley Software Group sells Data Seal hosting, targeted at states that have adopted UELMA. That’s only a dozen today, but will surely be close to 50 within a few years.

They’ve settled on a pricing structure that’s cheap enough to make it the obvious decision for states, and likely below many states’ threshold for putting a contract up to bid.

Now states can use Data Seal.

Silicon Valley Software Group makes money, states will save money, the public retains access to legal data. Everybody wins.

Open data wins rarely come quickly. They require demand by government, accepted standards to rely on, government buy-in to the proposed solution, and market forces to support that solution. In the case of UELMA, this win will come slower still, over the years that it will take for states to adopt and then implement UELMA. In the meantime, we’ll keep giving talks to state agencies, spreading the message that file verification is a solved problem, that they don’t need to fall back on PDFs, and that they don’t need to pay millions of dollars to a vendor to build a custom system. But they also don’t have to pay nothing. They can do something better—pay a little bit.